News: Underwriting Abraham

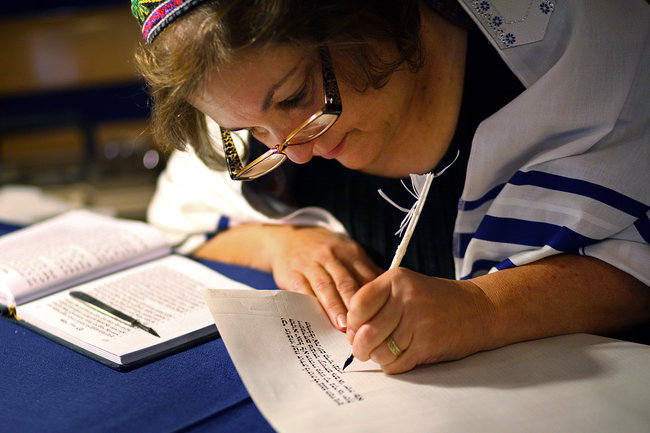

ON a recent Sunday in November, in the domed sanctuary of Congregation Beth Elohim in Park Slope, Brooklyn, a woman sat working, dipping a goose quill in black ink and touching it to a sheet of yellowish-white parchment.

She was wrapped in a wool scarf and a tallit, the prayer shawl used by Jews, and was several lines into scribing the 140th column of the Torah, the holiest book of the Jewish faith.

Every few moments, the woman, Linda Coppleson, pressed the broad edge of the quill’s nib into the parchment, creating a shining Hebrew letter. Then she added the impossibly thin lines of decorative flourish.

It was like a scene out of an old photograph of Jewish life, with a twist: Many of the letters Ms. Coppleson was writing were being “sponsored” by a member of the congregation. Part of a growing trend among synagogues, yeshivas and Jewish organizations, congregants are paying to underwrite the text of a new Torah. At Congregation Beth Elohim, the donation varies: $10,000 for one of the five books of the Torah; $3,600 for a parashah, or section; $1,000 for a name like Miriam, which might honor a dead relative; $540 for a word; and $180 for a letter.

Ms. Coppleson also had company as she worked: Congregants had been invited to help her ink the text they had sponsored by sitting next to her and placing a hand on her wrist as she wrote.

At Beth Elohim, a Reform congregation, the Torah is being produced to honor the synagogue’s 150th anniversary. But the goal of the underwriting projects generally is to raise more than just the cost of the Torah, which ranges from about $30,000 to more than $100,000, depending on the quality of the work.

In Albany, Congregation Ohav Shalom, a Conservative synagogue, raised about $100,000 beyond the cost of its new Torah; the extra money will be used for religious education and maintenance of the Torah scrolls, David Levine, the organizer, said.

At Temple Beth Sholom in Roslyn Heights, N.Y., large donors have already covered the cost of a new Torah, but fund-raising for the project is continuing, in part because the temple needs money to pay down the mortgage on its new preschool.

To organize these fund-raisers, a number of companies like Sofer OnSite, based in Miami Beach, Fla., and Stam in Brooklyn, act like Torah wedding planners, helping with the business of fund-raising and organizing scribes. A common technique is to produce price lists with different words or sections from the Torah. But the specific cost to dedicate a word, a phrase or a chapter of the Torah can vary greatly.

At Temple Beth Sholom, in a well-off Long Island suburb, it costs $36,000 to sponsor the Torah’s first sentence, $12,000 for the Torah’s first word and $180 for a letter. At Chabad of Harlem, which is raising money for what it says will be the first new Torah written for a Harlem synagogue in decades, a letter costs $18. Nothing about the contribution appears in the actual Torah; most often, a sponsor receives a certificate or is acknowledged on a plaque.

Writing a Torah is considered a holy obligation of all Jews — the 613th of the religion’s 613 commandments. In the digital age, meeting that obligation has sometimes become as easy as click and go. Visitors to the Web site of Misaskim, a relief organization based in Brooklyn, can enter their credit card details to underwrite a Torah dedicated to the memory of Leiby Kletzky, the 8-year-old boy killed in Borough Park in 2011. Or they can use the same method to dedicate a word in a Torah honoring Rabbi Noah Weinberg, the founder of Aish HaTorah, an educational organization based in Jerusalem.

“I am seeking someone to do the main dedication for $100,000,” said Rabbi Elazar Grunberger of Aish HaTorah, even though the scroll itself, he added, costs $50,000, and others have already donated.

“It only multiplies the mitzvah,” he said of the extra fund-raising, using the Jewish word for a good deed. “The extra money goes to the organization that is being benefited by this.”

At Beth Elohim, a synagogue popular with liberal, progressive Jewish families, Leslie Frishberg took on the job of leading the Torah-writing project. The synagogue has several damaged Torahs from the Holocaust and needs another intact one to use at services, she said.

First, she checked out what she called the professional “soup to nuts” organizing companies. But she felt put off by what she said was their commercial approach. “It’s almost like hiring a D.J. for your bar or bat mitzvah,” she said. “Do you want me to throw gifts? Do you want me to do a montage for you? The add-ins could make the Torah project go up to $200,000, easily.”

So Beth Elohim decided to organize the project itself. First, the synagogue sought out a female scribe, still a rarity in the Jewish world, in which the traditional understanding of Jewish law is that only devout Jewish men are allowed to be Torah scribes. Then, they decided to try to turn the idea of dedicating a word or phrase in the Torah from symbolic to concrete.

At many congregations, donors to Torah projects are invited to write or fill in with ink the outline of a random letter or two with the scribe at events that occur throughout the year that it generally takes to complete the 79,847 words of a Torah. But Beth Elohim wanted people actually to help write the words they had paid to dedicate.

The logistics are harder because Ms. Coppleson has to leave blank spaces in the text to fill in later. But Ms. Frishberg said, “For them to sit and scribe those actual words is incredibly meaningful.”

On Beth Elohim’s Web site, there is a shopping cart so people can pay for the word they are sponsoring. But there is also an apology in the F.A.Q. section: Noting that “ ‘Add to Cart,’ seems rather crass for fulfilling the mitzvah of writing in a Torah,” the site says that “our committee wrestled with the commercialization aspect of the project, and beg forgiveness that, as a congregant, you will see that this was a means to making the project accessible to our entire community as efficiently as possible.”

That concern, however, seemed to fade into the background during a daylong scribing ceremony on Nov. 18, held under a canopy, because welcoming a Torah is said to be like welcoming a bride under a huppah.

Guided by Rabbi Andy Bachman and other volunteers, families washed their hands, said blessings and put on prayer shawls before sitting next to Ms. Coppleson.

She explained the meaning of the letters or words they were about to write with her, and answered questions about the art of scribing.

Then she invited them to place a hand on hers as she wrote. “See what you did: you helped me write that letter!” she said to Elya Zucker, 3, who put her tiny hand cautiously on Ms. Coppleson’s wrist. “Good job!”

Most people that day had just paid the minimal amount to participate, writing whatever word or letter Ms. Coppleson was up to.

They received certificates listing what lines they had helped with, and will be notified when that section of the Torah is read next year, in case they want to help recite it. The synagogue has already raised enough to cover the cost of the project — about $90,000 — and the rest is creating a fund for the restoration and purchase of ritual objects, like prayer books, Ms. Frishberg said.

Elya’s father, Scott Zucker, 42, said the exact letter or word he and his family were writing didn’t matter. He was more personally invested in the fact that his son, Nathaniel, 7, wore the same tallit for the ceremony that Mr. Zucker had worn at his own bar mitzvah decades ago.

“Frankly,” he said of the Torah’s letters, “it felt like they are all pretty special.”